Recent history of the treasure trove

The Seuso treasure, which is indirectly connected with Hungary by many facts, appeared on the international art market at the very beginning of the 1990s. Since its appearance the trove has experienced many adventures, which ended with the repatriation to Hungary of the first part and the second part in spring 2014 and summer 2017, respectively.

In 1984 the treasure trove was offered for sale to the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. The then head of the Collection of Classical Antiquities at the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, János György Szilágyi, who happened to be in the museum, noticed the inscription “Pelso” on an object of the treasure (the so-called hunting or Seuso platter), which he immediately recognized as the Roman name of Lake Balaton. On his return to Hungary, he called professor of archaeology, András Mócsy’s attention to the treasure trove and the inscription on the platter. That was when Hungarian researchers first took note of the treasure, although no official steps were taken to discover the references it had to Hungary.

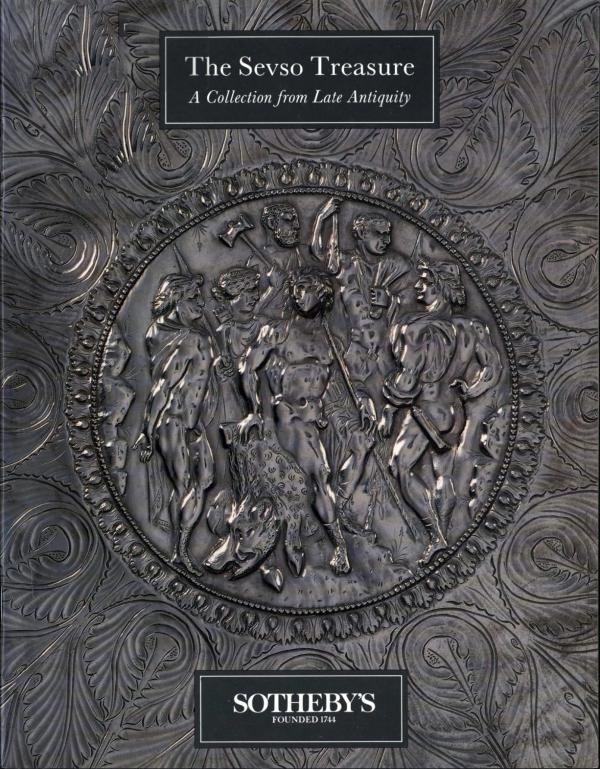

Then in 1990 the treasure trove was offered for sale by Sotheby’s, having been commissioned by a consortium headed by the British aristocrat Marquess of Northampton. It was in February 1990 that the first private display of the treasure was held at the New York headquarters of the auction house. Following the announcement of the auction, the treasure found itself in the focus of international interest. Soon Lebanon, Yugoslavia (later Croatia as legal successor represented the claim of the meanwhile dissolved state) and Hungary – recognizing the treasure find on the basis of the data gained in 1984 – announced their claim for ownership of the invaluable objects of art.

Preceded by a lengthy preliminary procedural phase, the court began the case about the right of ownership of the treasure in New York in autumn 1993. It was then that Hungarian researchers took note of the fact that there may be a connection between the four-legged, folding silver stand (quadripus) found in fragments on Szárhegy (belonging administratively to the village of Kőszárhegy), and the Seuso treasure. The stand perfectly matches the objects of the Seuso treasure regarding both the style and themes of its rich ornamentation, as well as its impressive measurements. The quadripus was discovered only a few kilometres from Lake Balaton, Pelso as named on the Seuso platter. The residence of the former owner of the treasure must have been near the lake too. Although in the 19th and 20th centuries a number of excavations were conducted at the site of the discovered silver stand, considered as a unique archaeological find, other fragments belonging to the stand have to date not been found.

It soon turned out that the police had been investigating a murder committed in December 1980 near where the fragments of the silver stand were discovered in 1878. The victim was 24-year-old József Sümegh, whose compulsory military service was coming to an end. His body was found hanging in a wine cellar. The young man collected coins and antiquities. He was said to have found an enormous silver treasure before starting his military service and he may have been killed for that. During the police investigation traces of a filled-in pit were observed in the wine cellar, the scene of the crime. Its exploration with archaeological methods actually took place. As to its measurements, the copper cauldron, a part of the Seuso treasure in which the known silver objects were hidden, perfectly fits the pit. This has subsequently been verified by an authentication excavation.

Before the court case in New York the export licences authenticating the Lebanese origin of the treasure proved to be false, but Lebanon had in the meantime renounced its claim for ownership. Marquess of Northampton, in charge of the consortium, proved that he had no knowledge of the origin of the Seuso treasure at the time of purchase, therefore he was able to remain in possession of the find. The Hungarian party intended to put forward the comparative silver and soil samples, the results of the police investigation and the Kőszárhegy quadripus gathered during the preliminary procedure before the jury in 1993-1994. However, this was not granted by the court for reasons of legal practice, and in the end the court rejected the claim for ownership by all the plaintiffs. Thus the right of possession remained with the consortium headed by Marquess of Northampton. Nevertheless, the objects became unsellable on the art market due to their questionable origin.

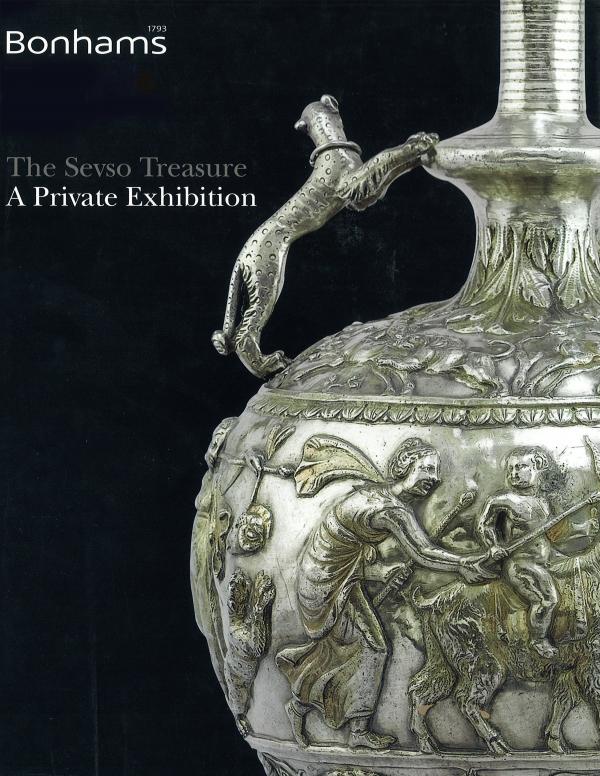

Later, in October 2006, an attempt was made to sell the treasure again, but that was unsuccessful. The treasure find was put on display for an invited audience for the second time in October 2006 at the London headquarters of Bonhams auction house. The private exhibition lasted only a few days. The find was then divided into two parts. In 2012 a Hungarian individual made an attempt to purchase the treasure unsuccessfully. Finally the Hungarian state began negotiations about acquiring half of the treasure trove, including the Seuso platter and the copper cauldron. As a result of the rounds of negotiations lasting some two years, the first half of the treasure, which was in the possession of the inheritors of Peter Wilson, the former president of Sotheby’s, was transported back to Hungary. Regaining the second half of the treasure possessed by Marquess of Northampton was the result of yet another round of negotiations lasting several years. Finally, it was repatriated in the summer of 2017. In harmony with the international agreements on illegal art trade, the Hungarian state paid a compensation fee for both parts of the treasure: 15 million euros for the first half and 28 million euros for the second, more valuable half containing more ornamented vessels.

Despite all the coincidences, the facts and evidence mentioned above refer to the treasure having been discovered on a site in Hungary only indirectly for the time being. The clarification of find-spot and circumstances of the Seuso treasure can be expected only from the results of new comprehensive and thorough scientific (archaeological, art historical and archaeometric) analyses begun in 2014, and of police investigations. Not only a never-before existing opportunity has opened for all this by repatriation the currently known fifteen pieces of the set, but Hungary has also obtained unique objects of art representing the highest artistic standard of the late Roman imperial age.