Roman wall paintings

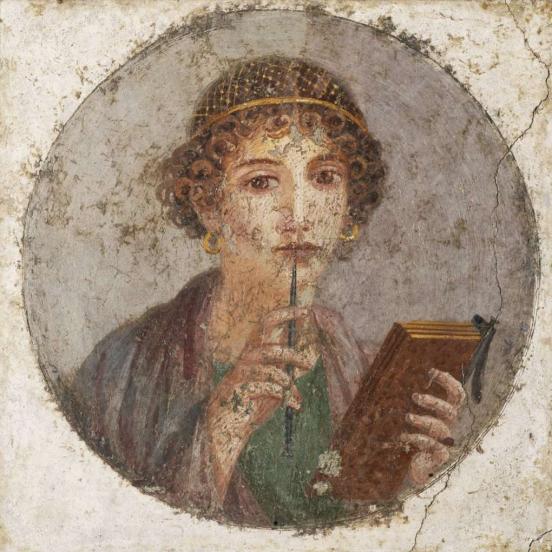

Most people identify Roman frescos with Pompeii, since that is where most early imperial paintings in good condition are known from. Yet that is mostly due to chance, the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, which covered the settlements on the southern part of the Bay of Naples with lava and volcanic ash. Many of the works discovered in the 18th century are today regarded as well-known works of Roman art: such is a woman’s portrait in medallion with wax tablet and stylus discovered in Pompeii, which art connoisseurs identified with Sappho in old times, although there is no evidence that the painting indeed represents the famous Greek poetess. An other famous painting was found in Stabiae. In this a charming female figure in a floaty, yellow dress is walking with a green background behind her. She is depicted with her back to the viewer which, given the fondness for experimenting with virtuosic poses, was not too unusual in Hellenistic and Roman painting.

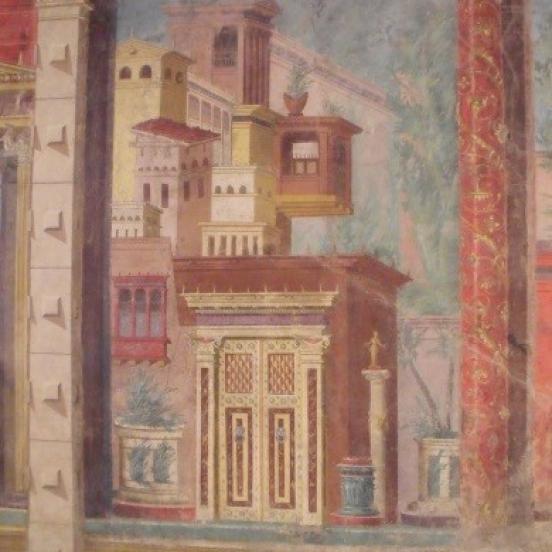

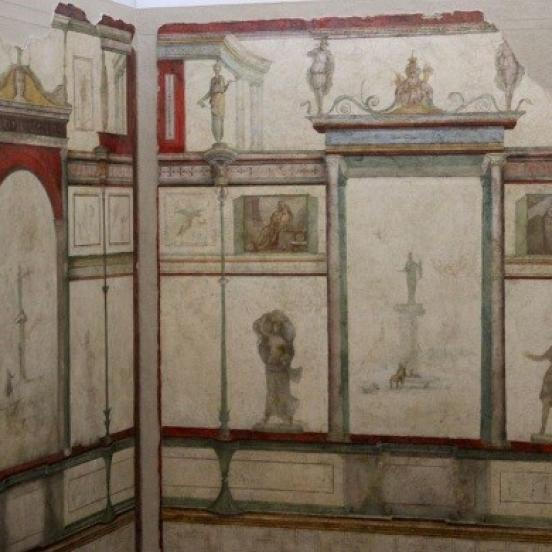

The frescos in Pompeii, Stabiae and the other sites in the vicinity of Mount Vesuvius fit in a long tradition of painting. Today wall paintings surpassing in quality those of Pompeii are known from the city of Rome, as well as the eastern part of the Mediterranean. This suggests that we can talk about a genre of an era that was widely spread (1st century B.C. – 1st century A.D.). On the basis of the Pompeii finds, decorative wall painting used in interiors were divided to phases already in the 19th century and they are still referred to as the “four styles of Pompeian wall painting”. The ‘first’ of these decorative systems applied not only in Pompeii, but actually existing side by side elsewhere simply meant that noble building materials (colourful stone slabs) were imitated by painting in an ornamental arrangement. Applying optical illusion, the ‘second style’ created virtual spaces making the viewer think that there are infinite landscapes, buildings and gardens beyond the walls. The ‘third style’ simplified the fictitious architectural elements used in the second style to slender dividing components. It presented still life, landscapes and framed scenes between them as “a picture in the picture”. The ‘fourth style’ fused the optical illusion of the ‘second style’ with the daring abstractions of the ‘third’ by a regular disarray of the feeling of real space.